PSY 652: Research Methods in Psychology I

The Logic of Null Hypothesis Significance Testing

Today’s Focus

The Experiment

Participants imagined being athletes competing in a boulder-sliding game against an opponent named Blorg. The goal was to slide a boulder farther on ice to win a prize.

A Special Boulder

Participants could rent a “special boulder” — a possibly advantageous upgrade expected to improve performance.

The Conditions

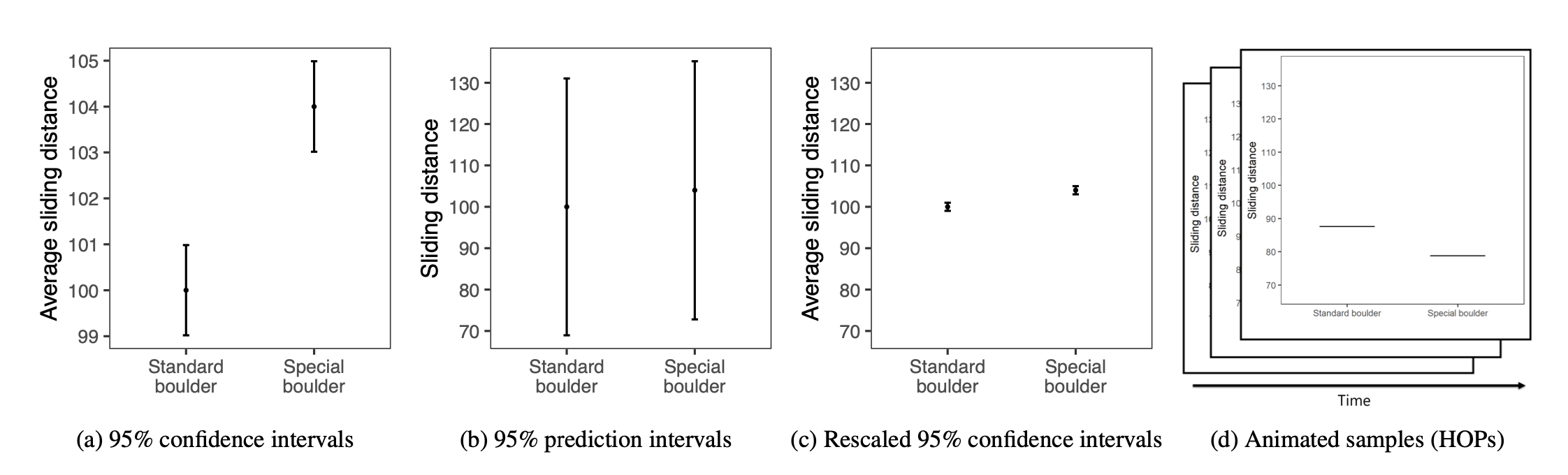

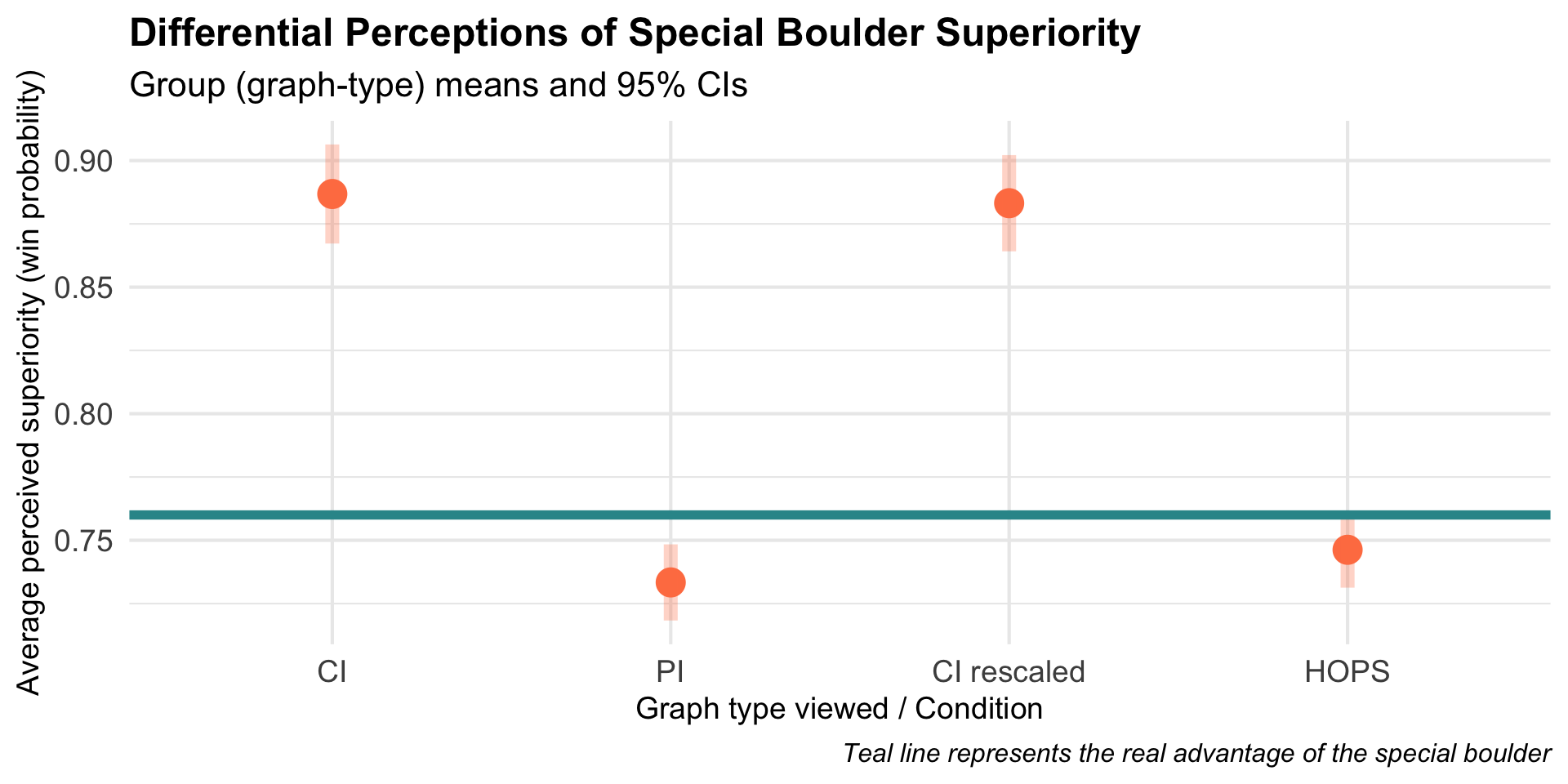

To help decide whether to rent the special boulder, each participant saw one of four uncertainty visualizations summarizing prior results.

The Outcome

After viewing their assigned visualization, participants estimated the probability that using the special boulder would help them win. We’ll refer to this as perceived win probability.

The Data

- graph_type: visualization type (CI, PI, CI rescaled, HOPS) — randomly assigned

- superiority_special: perceived probability that the special boulder would win (0–1)

Visualize the Data

Our Research Question

Let’s focus on the PI condition.

Research Question

Did participants who saw the PI visualization accurately perceive the boulder’s true advantage (actual winning probability = 0.76) — or did their perceived advantage systematically differ?

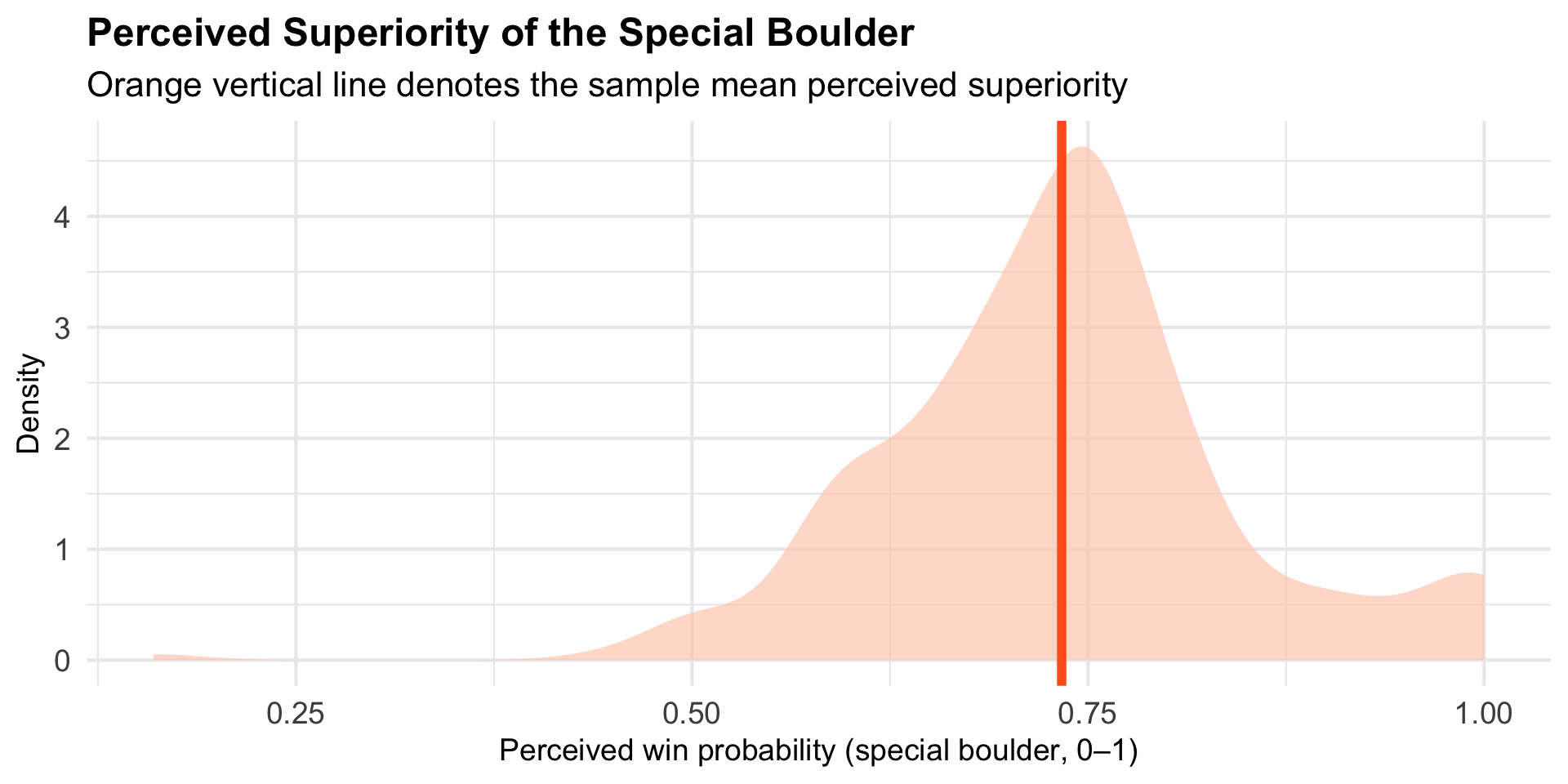

Visualize the Raw Data

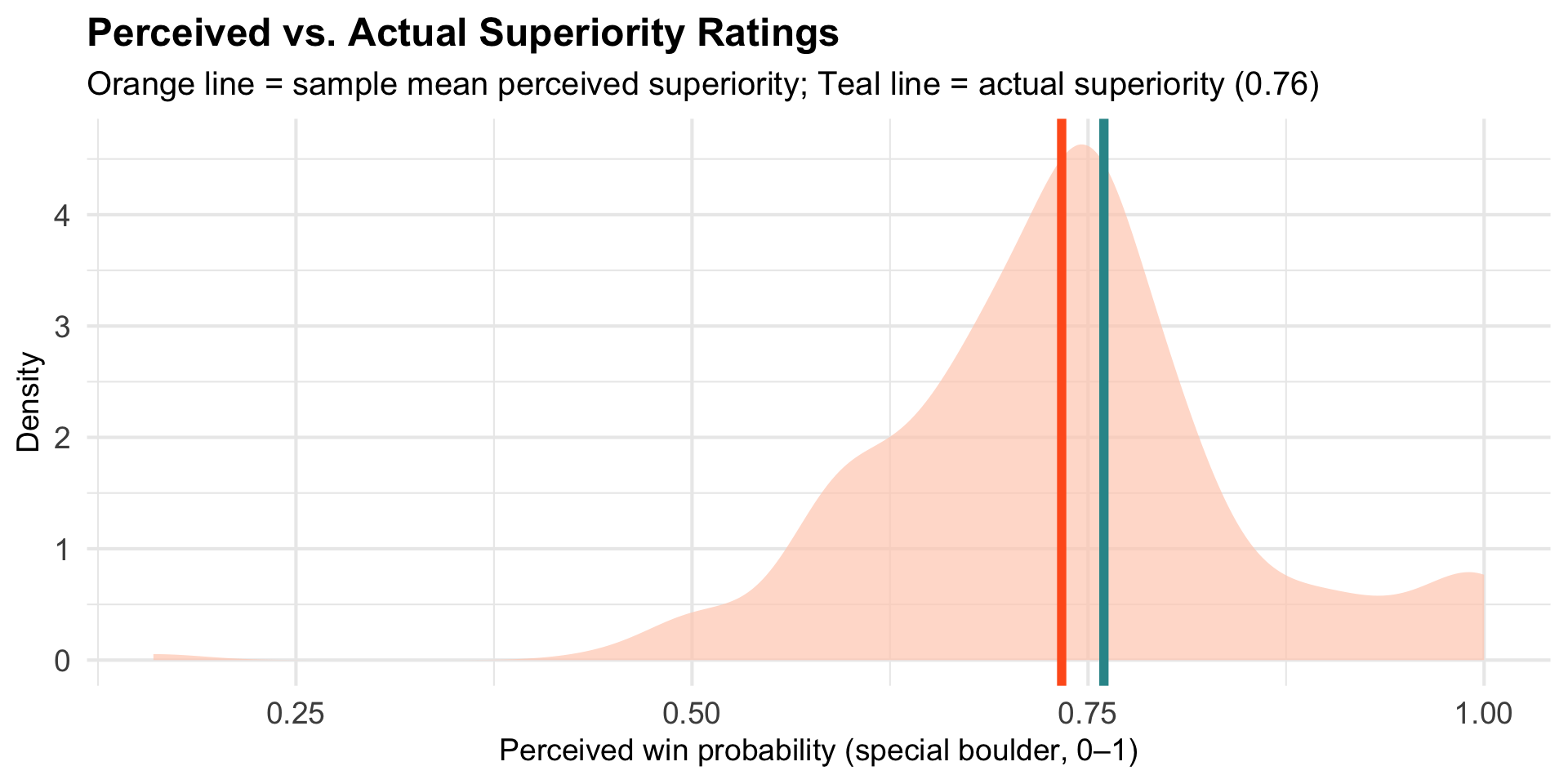

Overlay the Actual Superiority

Estimation of the Population Parameter

Using our sample, we can estimate the population parameter of interest.

That is, the true mean perceived win probability in the population, denoted \(\mu\).

How Much Uncertainty Is in This Estimate?

- Our sample is ONE realization of the data — each potential sample that we would draw would produce a different mean.

- Therefore, we need a method to estimate uncertainty around this mean.

- We’ve learned a variety of ways to quantify this uncertainty — for example, we can use bootstrap resampling.

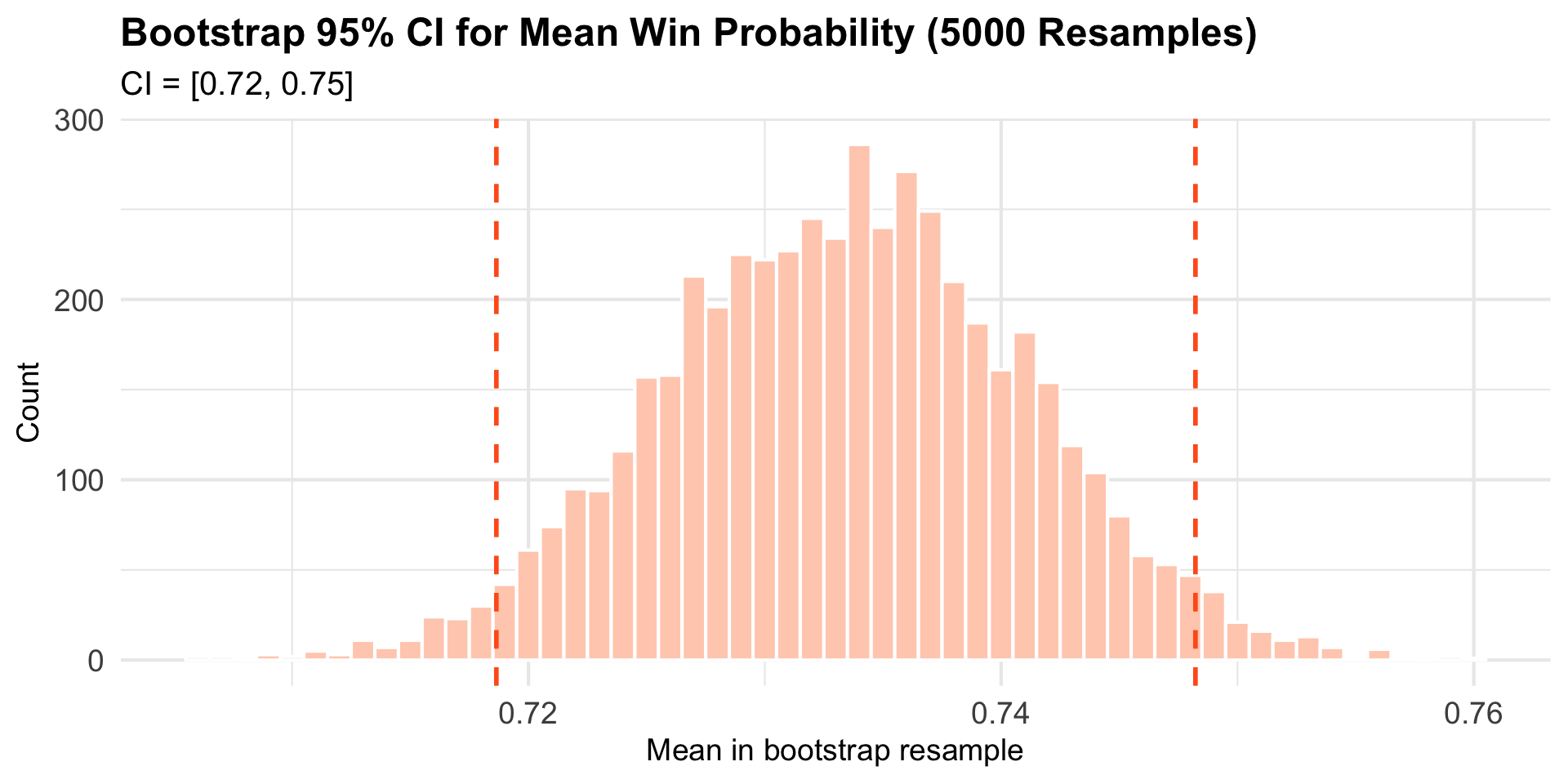

Bootstrap Resampling to Quantify Sampling Variability

Interpretation: We’re 95% confident that the population mean perception of superiority, \(\mu\), lies within this range.

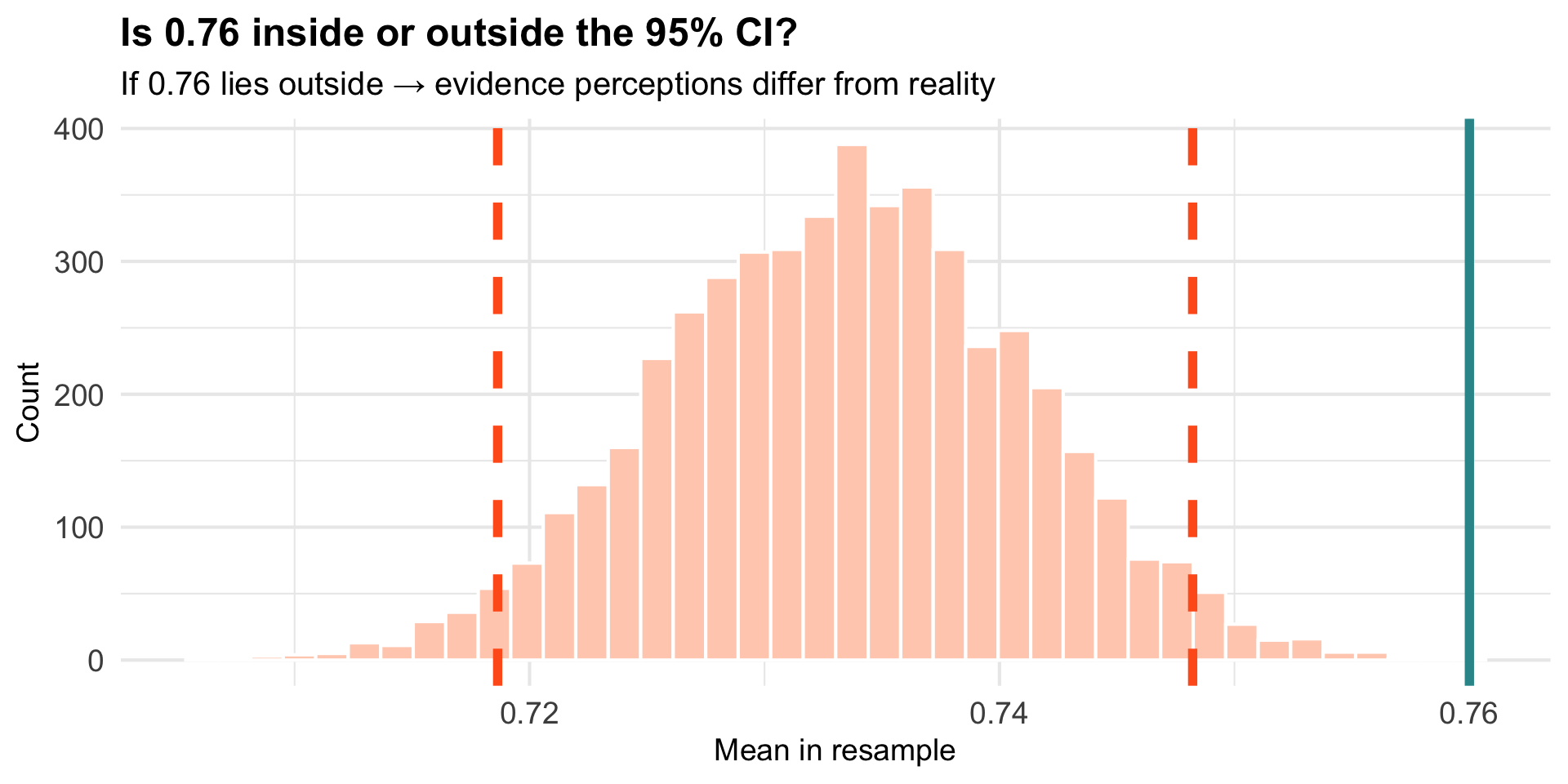

Where Does the Actual Superiority (0.76) Fall?

A Different Question: Starting with a Skeptical Stance

So far: We’ve estimated \(\mu\) and created a CI around our estimate.

Now: What if we start from a position of skepticism?

The Skeptic’s Question

“I think participants perceive the boulder accurately (i.e., \(\mu = 0.76\)). Your sample just happened to be different by chance. Can you prove me wrong?”

This flips our approach: instead of estimating the unknown, we assume a specific value and ask whether our data are compatible with it.

Null Hypothesis Significance Testing (NHST)

The Logic:

- State a “null hypothesis” (\(H_0\)): a specific claim about the population we’ll test

- State an “alternative hypothesis” (\(H_A\)): what we suspect instead

- Assume \(H_0\) is true, then ask: “How surprising is our sample under this assumption?”

- If our sample would be very rare under \(H_0\), we have evidence against it

Our Hypotheses

Important

\(H_0\): \(\mu = 0.76\): Participants accurately perceive the boulder’s true advantage.

\(H_A\): \(\mu \neq 0.76\): Participants’ perceptions systematically differ from reality.

Key insight: We’re not estimating \(\mu\) anymore — we’re testing a specific claim about what \(\mu\) equals. We’ll refer to this null hypothesis value as \(\mu_0\).

The Core Question of NHST

The Question

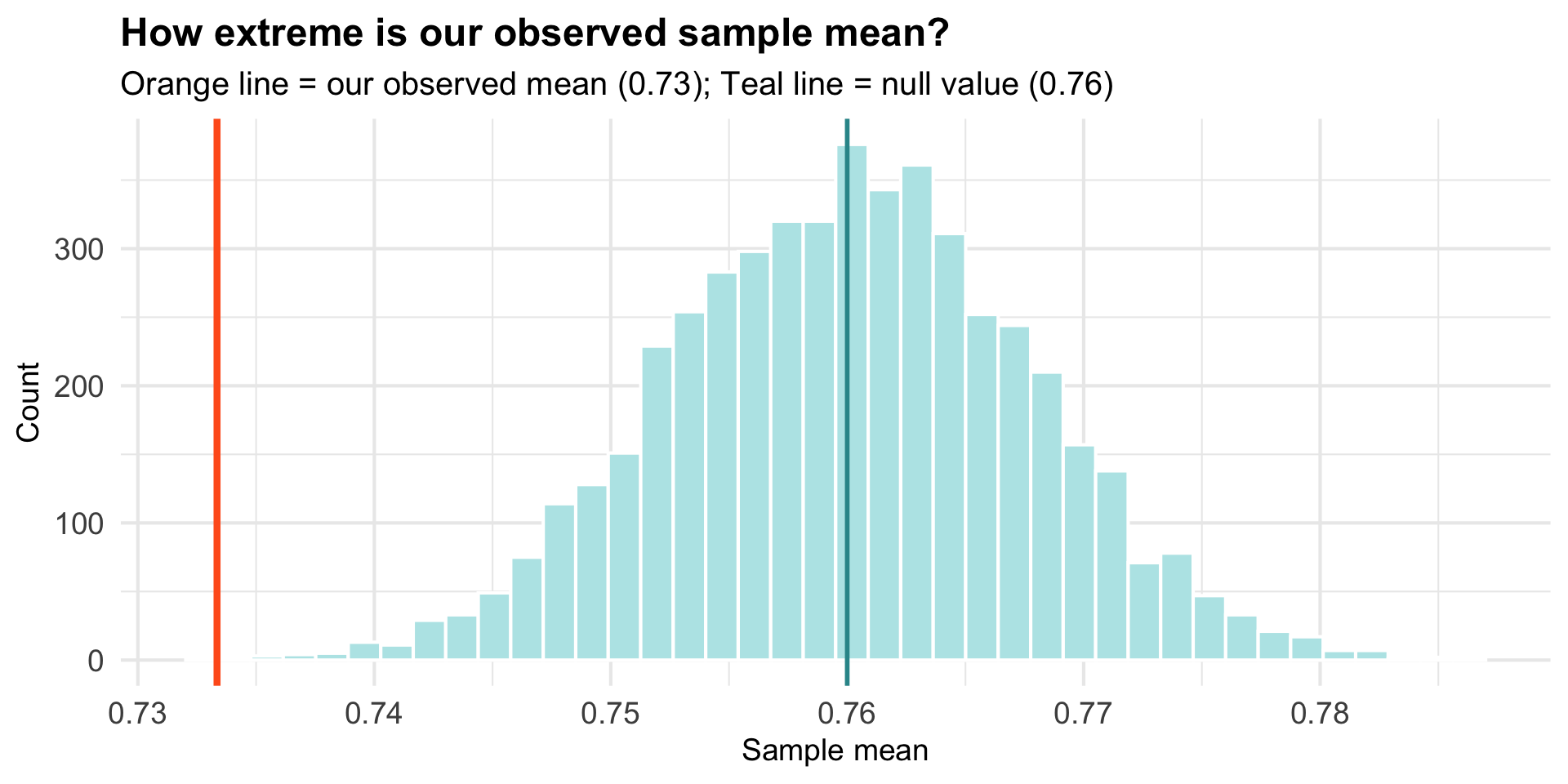

IF the null hypothesis were true (i.e., people really do perceive accurately, so \(\mu = 0.76\))…

HOW LIKELY would it be to observe a sample mean as far from 0.76 as ours (\(\bar{x}\) = 0.73)?

To answer this, we need to know what sample means would look like if \(H_0\) were true.

Visualizing the Null World

We already created a bootstrap sampling distribution that shows the variability we’d expect in sample means, centered at our observed mean.

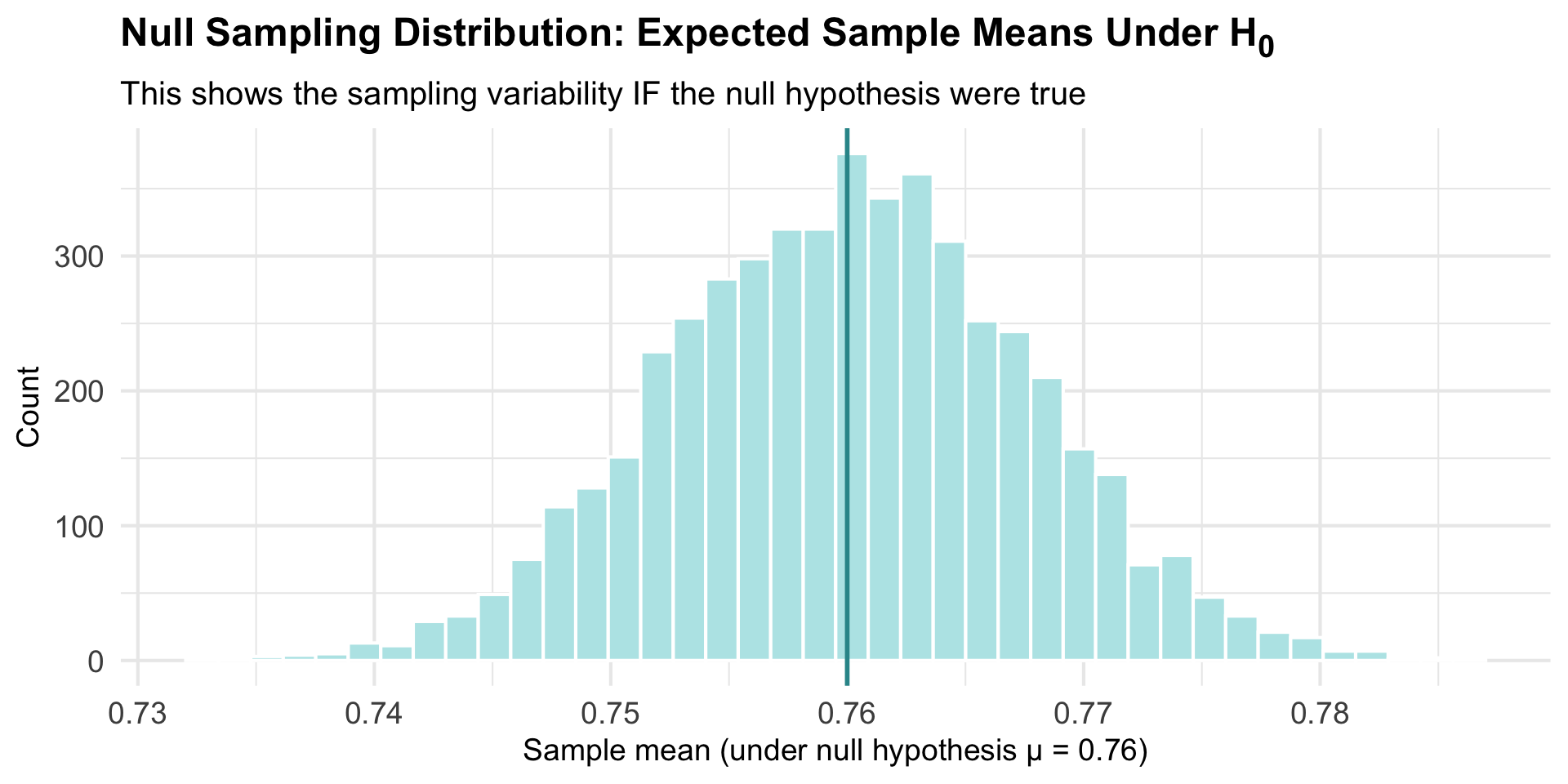

Here’s the key question: What would this sampling distribution look like if the null hypothesis were true — that is, if the true population mean were actually 0.76?

Simple answer: We just shift our entire bootstrap distribution to be centered at 0.76!

The Sampling Distribution Under the Null Hypothesis

This is our “null sampling distribution” — what sample means look like when \(H_0\) is true.

Where Does Our Actual Sample Fall?

Our observed mean (\(\bar{x}\) = 0.73) seems unusual under the null hypothesis.

Quantifying “How Unusual”: The p-value

Important

The p-value is the probability of observing a sample statistic as extreme or more extreme than what we actually observed, assuming \(H_0\) is true.

It is a conditional probability: \[P(\text{data as extreme or more} \mid H_0 \text{ is true})\]

This reads as: “The probability of getting data this extreme (or more), given that the null hypothesis is true.”

We can count the number of bootstrap resamples from the null world that produce an estimate as extreme or more extreme than our observed sample, and compute the proportion. This is the p-value.

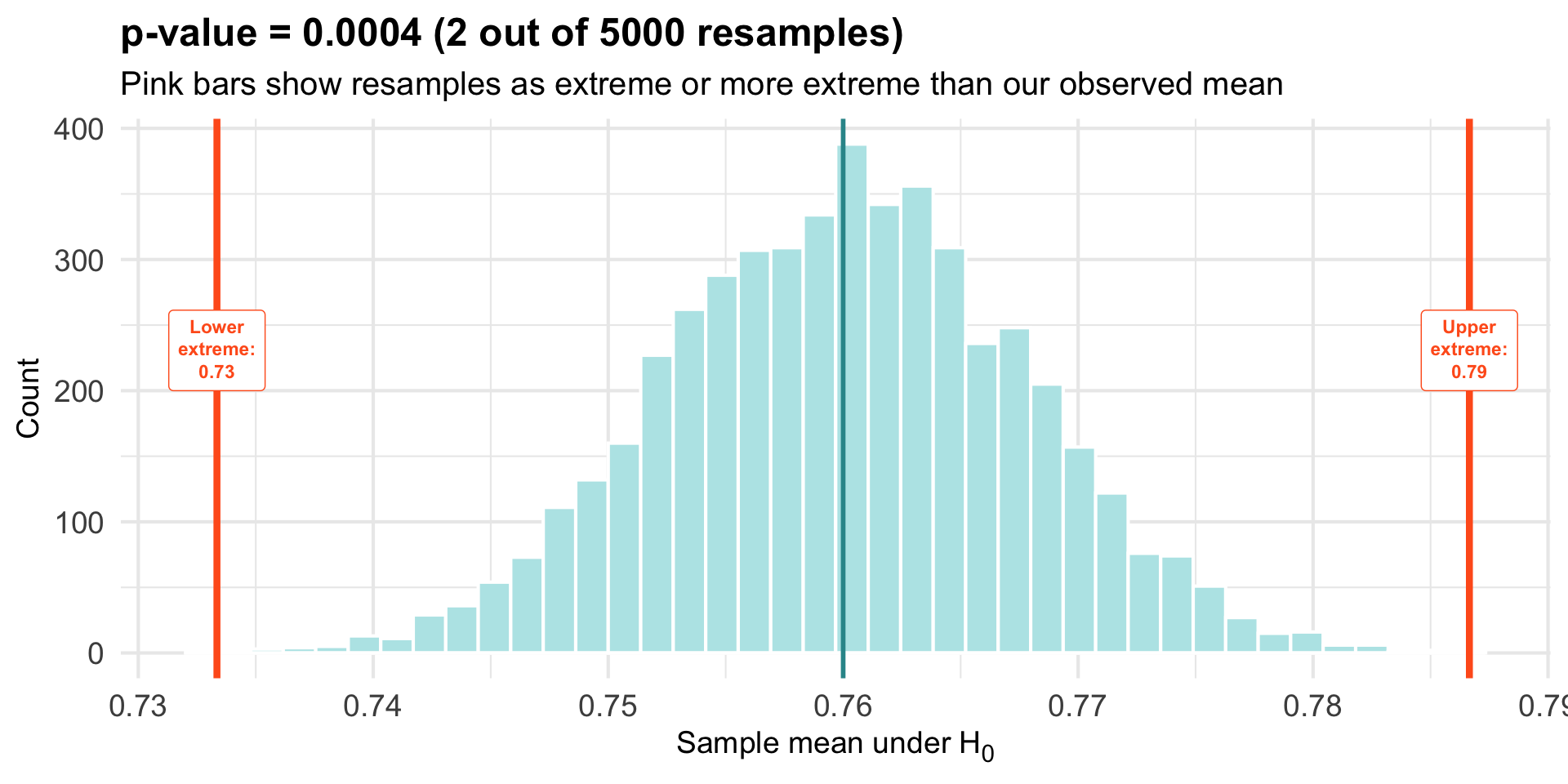

Graphical Depiction of p-value

Both Tails

We look at both tails of the null distribution because our alternative hypothesis is two-sided — we’re testing whether the observed sample mean is either much smaller or much larger than what we would expect if the null hypothesis were true.

The bounds for these regions were computed by taking the null mean (μ₀) and moving an equal distance to the left and right, based on how far the observed mean is from μ₀:

Lower bound = μ₀ − |observed mean − μ₀|

Upper bound = μ₀ + |observed mean − μ₀|

This ensures both tails capture outcomes that are at least as extreme as what we actually observed, regardless of whether the deviation was above or below the null mean.

Interpreting the p-value

p = 0.0004

Interpretation

If the null hypothesis were true (participants perceive accurately), we’d observe a sample mean as extreme as ours in only about 0.04% of samples.

This is quite rare — suggesting our data are not very compatible with the null hypothesis.

Conventional threshold: If \(p < 0.05\), we typically conclude there’s sufficient evidence to reject \(H_0\).

The Connection to Our CI Approach

Notice the parallel logic:

| Estimation Approach | NHST Approach |

|---|---|

| Create CI around our estimate | Create null sampling distribution around hypothesized value |

| Check if 0.76 falls outside the CI | Check if our sample falls in the extreme tail of null sampling distribution |

| 0.76 is outside the CI → evidence of difference | p < 0.05 → evidence against the null |

Both approaches reach the same conclusion — just asking the question differently!

What Could Go Wrong? Four Possibilities

When we make a decision based on our data, there are four possible outcomes:

| Reality: \(H_0\) is TRUE | Reality: \(H_0\) is FALSE | |

|---|---|---|

| Decision: Reject \(H_0\) | ❌ Type I Error (False Positive) |

✅ Correct Decision (True Positive) |

| Decision: Fail to Reject \(H_0\) | ✅ Correct Decision (True Negative) |

❌ Type II Error (False Negative) |

We can never know for certain which scenario we’re in — but we can control how often we make errors.

Type I Error: Crying Wolf

Type I Error (α)

Rejecting \(H_0\) when it’s actually true

In our study: Concluding perceptions differ from reality when they actually don’t.

Example: The null is true (\(\mu = 0.76\)), but we happened to get an unusual sample just by chance, leading us to incorrectly reject \(H_0\).

We control the Type I error rate by setting a threshold called alpha (α).

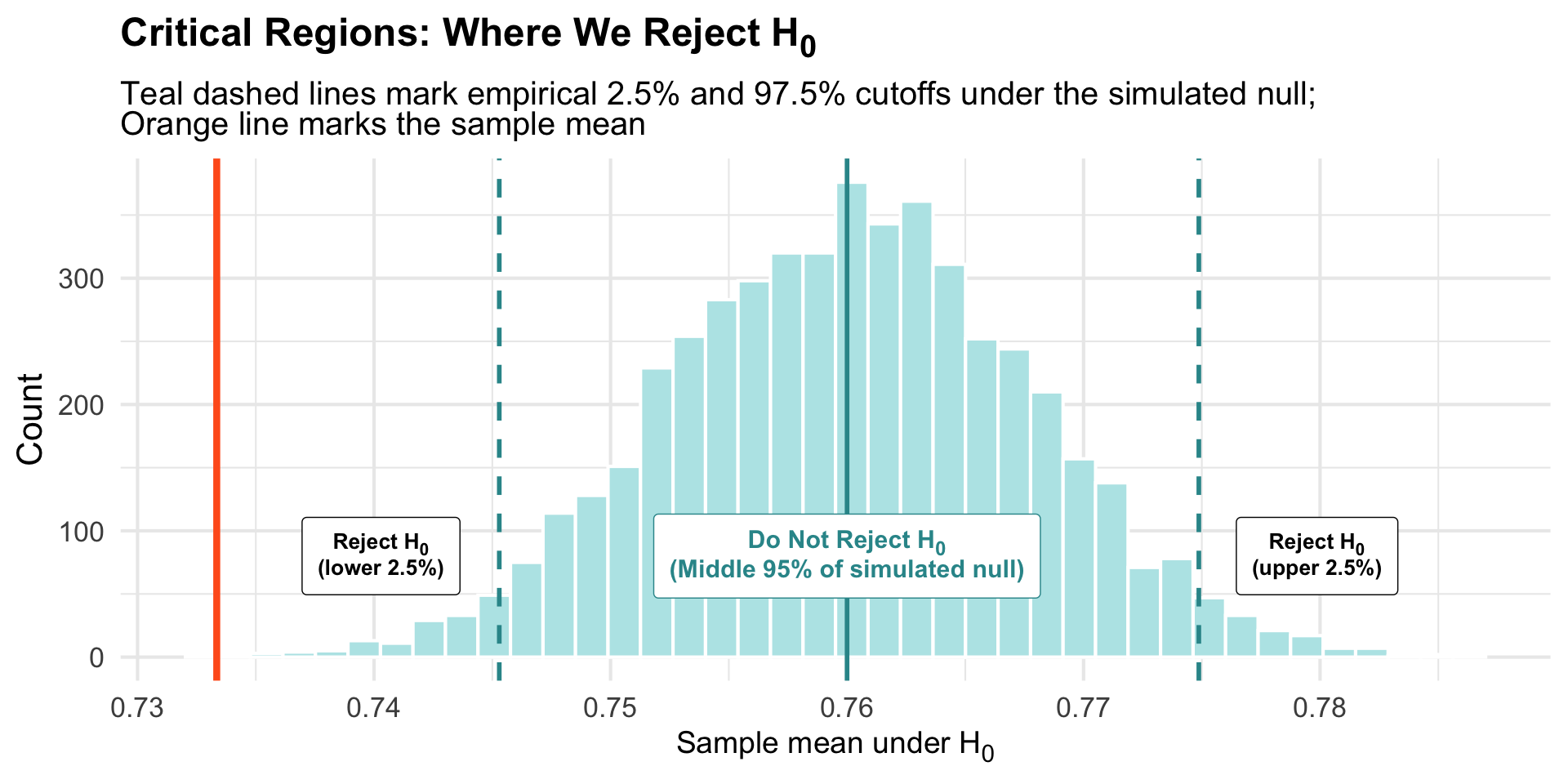

Connection to confidence intervals: When we set α = 0.05 for hypothesis testing, this corresponds to using a 95% confidence interval for estimation. Both approaches use the same threshold — keeping the most extreme 5% (2.5% in each tail) as our criterion for “unusual” results.

Setting Alpha

Alpha (α): The Significance Level

α = maximum Type I error rate we’re willing to tolerate

Convention: α = 0.05 (two-tailed). Should be selected based on the study scenario and should always be set a priori.

What this means: If the null hypothesis is true, we’re willing to incorrectly reject it in at most 5% of studies.

This is why we compare p-values to 0.05:

When α = 0.05:

- If \(p < 0.05\): Reject \(H_0\) (result is “statistically significant”)

- If \(p \geq 0.05\): Fail to reject \(H_0\)

Type II Error: Missing a Real Effect

Type II Error (β)

Failing to reject \(H_0\) when it’s actually false

In our study: Concluding perceptions are accurate when they actually differ.

Power = 1 - β = probability of correctly detecting an effect when it exists

Type II errors are harder to control directly, but we can reduce them by:

- Increasing sample size

- Using more precise measurements

- Having a larger true effect size

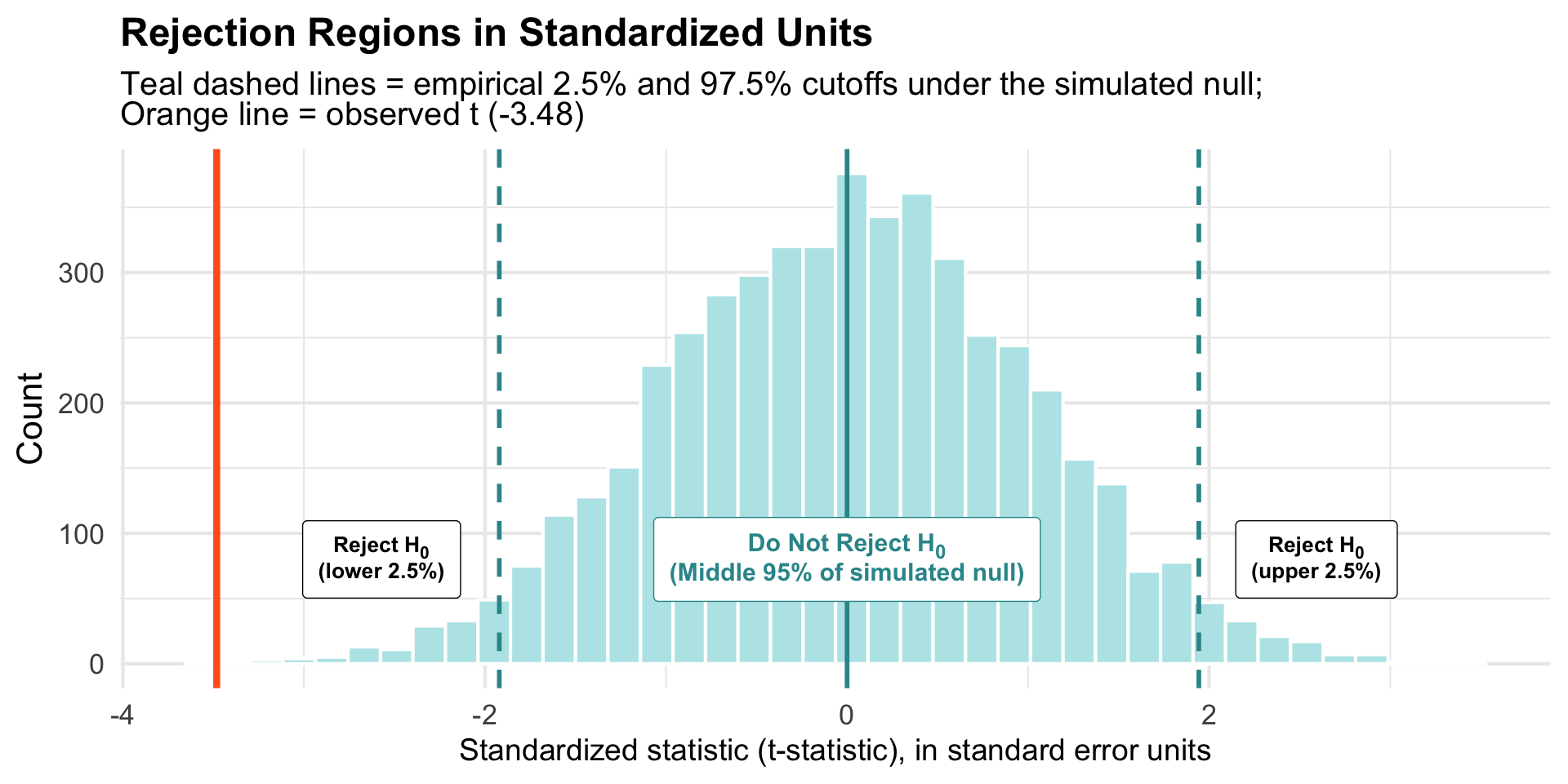

Visualizing Alpha on Our Null Sampling Distribution

Our observed mean (orange) falls in the rejection region → statistically significant.

The Problem: Different Studies Need Different Null Sampling Distributions

Each research question has its own:

- Null hypothesis value (0.76, 0, 100, etc.)

- Sample size

- Variability

Challenge: Hard to compare results across studies or build general rules.

Solution: Use a standardized scale that works for any research question!

Standardization: Creating a Universal Scale

Key insight: Instead of looking at raw means, express how far our sample is from \(H_0\) in standard error units.

To do this, we calculate the standard deviation of the sampling distribution (i.e., the standard error):

- Mean in sample: 0.7333

- Standard Error (SE): (The standard deviation of the sampling distribution) 0.0077

Standardized difference: \[\frac{\bar{x} - \mu_0}{SE(\bar{x})} = \frac{0.7333 - 0.76}{0.0077} \approx -3.48\]

Our sample mean is about 3.48 standard errors away from the null value. We commonly refer to this standardized difference as the t-statistic or t-ratio.

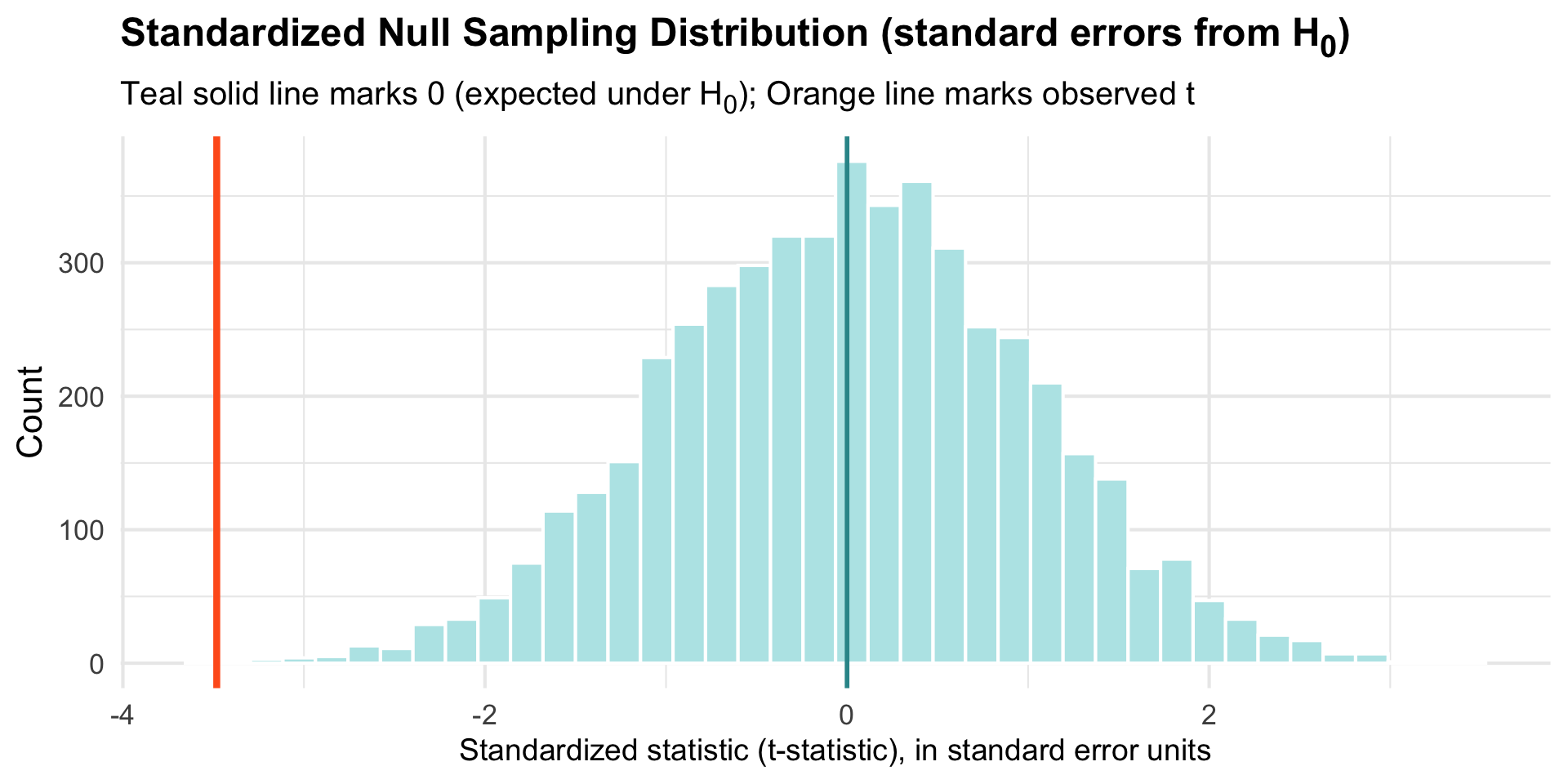

Standardizing the Null Sampling Distribution

Advantage: Now centered at 0 with a standard scale we can use universally!

Critical Regions on the Standardized Scale

The Mathematical Shortcut: Student’s t-Distribution

Good news: Under certain assumptions, we don’t need simulation!

Key Assumptions

- Random sampling from the population

- Independence between observations

- Normality: Population is normally distributed (or large sample via Central Limit Theorem (CLT))

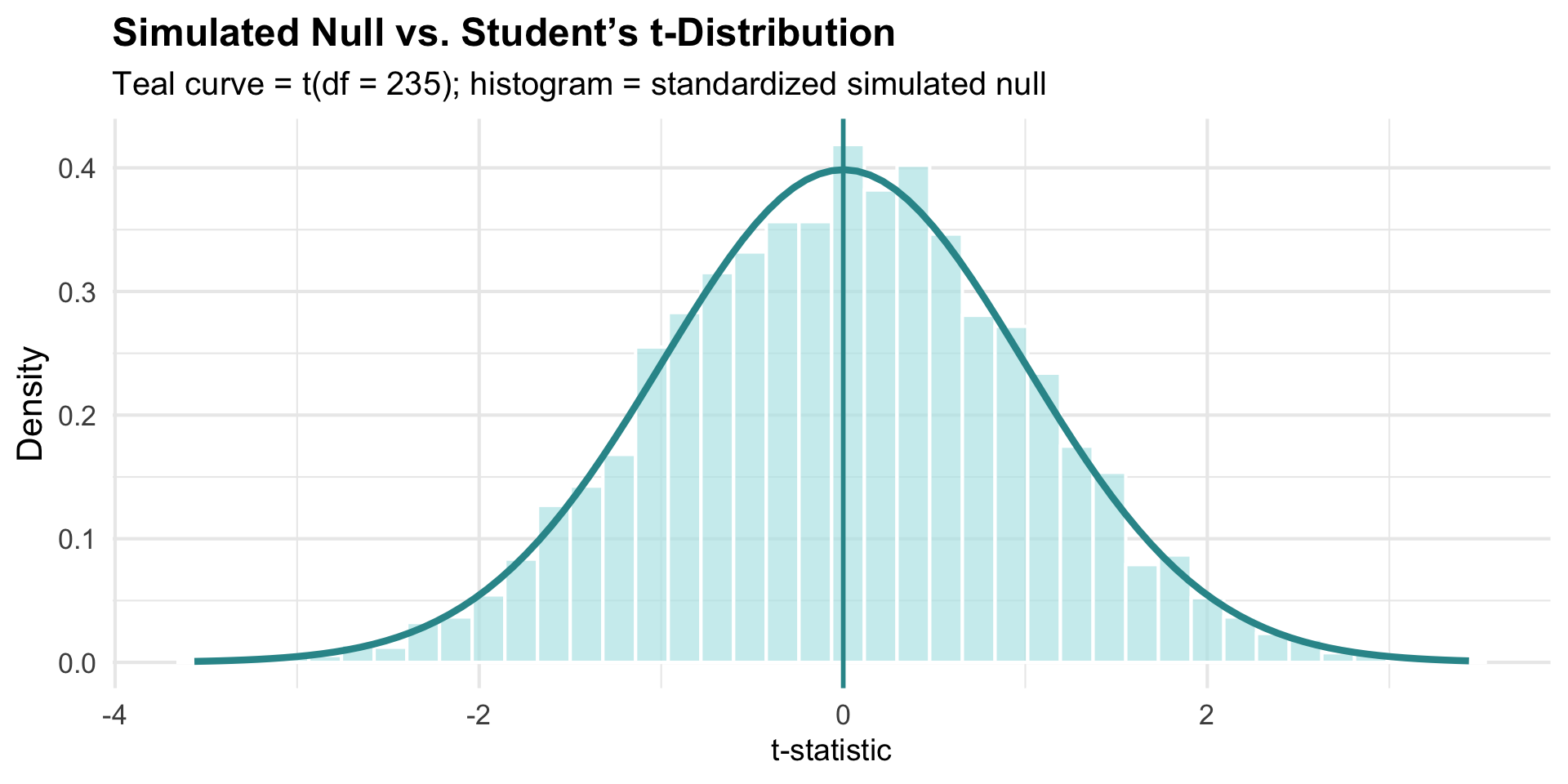

When these hold, the standardized null sampling distribution follows a known mathematical form: Student’s t-distribution with \(df = n - 1\) degrees of freedom (for estimating a population mean).

Comparing Simulated vs. Theoretical Distribution

They match closely.

The Parametric Approach: No Simulation Needed

Instead of bootstrapping to find SE, we can calculate it directly. For a mean:

\[SE(\bar{x}) = \frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}\]

where \(s\) is the sample standard deviation, and \(n\) is the sample size.

For our data:

\(SE(\bar{x}) = \frac{0.1173}{\sqrt{236}} = 0.0076\)

The Parametric t-statistic

Parametric t-statistic: \[\frac{\bar{x} - \mu_0}{SE(\bar{x})} = \frac{0.7333 - 0.76}{0.0076} \approx -3.49\]

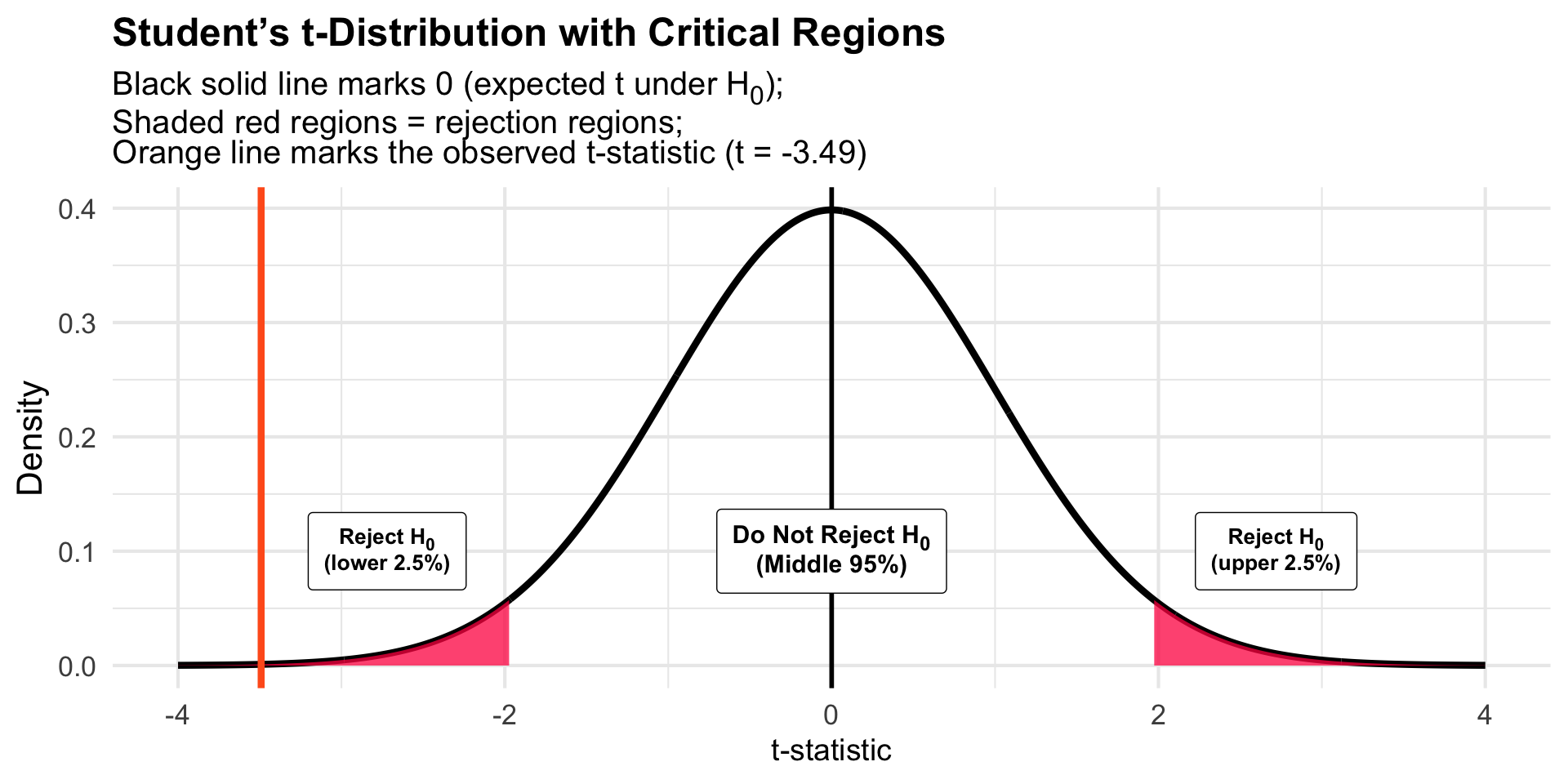

Finding the Critical Values

For a two-tailed test with \(\alpha = 0.05\) and \(df = 235\), the critical t-values are:

Map the Critical Values onto the Student’s t-Distribution

Since \(|t| = 3.49 > 1.97\), we reject \(H_0\).

Compute p-value Directly

Using the observed t-statistic, the two-tailed p-value is:

p-value = 0.000574Interpretation: The probability of observing a t-statistic as extreme as -3.49 (or more extreme in either direction) is 0.000574 if the null hypothesis were true.

A One-Sample t-test

Interpretation:

- \(t(235) = -3.49\), \(p = 0.00057\)

- Our observed mean (0.733) is significantly different from 0.76

- 95% CI: [0.72, 0.75]

Conclusion: Participants who saw the PI visualization underestimated the special boulder’s advantage.

Summary: The NHST Framework

The complete process:

- State hypotheses: \(H_0\) vs. \(H_A\)

- Set α level (often 0.05 — two-tailed — with 0.025 in each tail)

- Calculate test statistic

- Find critical values using

qt()and/or calculate p-value usingpt() - Make decision:

- If \(p < \alpha\) (or \(|t|\) exceeds the critical value): Reject \(H_0\)

- If \(p \geq \alpha\) (or \(|t|\) does not exceed the critical value): Fail to reject \(H_0\)

Key insight: A 95% CI that excludes the null value, a p-value < 0.05, and a t-statistic in the rejection region all tell the same story!

Wrapping Up

Remember:

- NHST starts with a skeptical stance (the null hypothesis)

- We evaluate whether our data would be surprising under that assumption

- Standardization allows us to compare results across different studies

- The t-distribution provides a theoretical shortcut when assumptions hold

- The p-value is NOT the probability that the null hypothesis is true — it is the probability of obtaining a test statistic as extreme or more extreme than in the observed sample, IF the null hypothesis is true.