Apply and Practice Activity

Crude and Adjusted Estimates of Hypertension

Introduction

In Module 2 we learned about calculating crude statistics. Crude statistics refer to raw, unmodified data that provide a general overview without accounting for any external factors or variables that might influence the results.

For example, using pooled NHANES data from 2005 to 2015, 44.5% of people age 18 and older meet the criteria for hypertension as defined by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) 2017 guidelines. These guidelines classify an adult as having hypertension if systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mm Hg, or the individual self-reported antihypertensive medication use.

Imagine that our goal is to use the NHANES data to compute an estimate of hypertension among US adults. This crude estimate of hypertension of 44.5% based on NHANES data offers an initial glimpse but may not portray the most accurate or meaningful insight due to the lack of normalization or adjustment for relevant influences. For example, if the NHANES participants differ in important ways from the general US population in terms of age distribution (e.g., if older people are less likely to participate in NHANES), race/ethnic distribution (e.g., if certain racial/ethnic groups are over represented in NHANES), or sex (e.g., if females are more likely to participate in NHANES compared to males) then our crude estimate of 44.5% based on the NHANES data may not be an accurate estimate of the rate of hypertension among US adults.

Adjusted statistics, on the other hand, refine these raw figures by controlling for or taking into consideration various influencing factors, such as the demographic variables described above. One very common adjustment for health outcomes is an age adjustment.

Age adjustment is crucial because the prevalence of certain health conditions, like hypertension, can vary significantly with age. That is, hypertension risk increases with age. Therefore, a population with more older adults might show a higher crude prevalence of hypertension compared to a younger population.

A simple example

Let’s walk through the steps to compute an age-adjusted statistic using a simple example to begin. Please download this worksheet to record your work.

Step 1

Select Salient Age Groupings: In calculating an age-adjusted prevalence, salient age groups are first selected. In this example, we’ll use the following four groups: 18-45, 46-64, 65-74, and 75+.

Step 2

Compute the Age-Specific Prevalence in Each Age Grouping: Next, the age-specific prevalence in the groups is computed. In the NHANES data, those age-specific prevalences of hypertension are as follows (where age_category provides the age group and estimate provides the percentage of people in the age group with hypertension):

Here, we see that the prevalence of hypertension increases with age. Only about 23% of adults age 18-44 are classified as having hypertension — while among those 75 and older the prevalence of hypertension increases to nearly 83%.

In the provided worksheet under Part 1, record the estimate for the percentage of people with hypertension in each age category in the column labeled unadjusted_estimate.

Step 3

Select a Standard Population: To compute an age-adjusted prevalence, we need to select a standard population. Using a standard population is crucial for age adjustment because it provides a consistent reference point that allows us to compare different populations on an equal footing. Age distributions can vary widely between populations, and without adjusting for these differences, our estimates might be skewed by the age structure of the sample. By applying the age distribution of a standard population, we can control for these variations and obtain an estimate that more accurately reflects the true prevalence of a condition, independent of age differences. This standardization is essential for making fair and meaningful comparisons across different groups or time periods.

In Public Health, a standard population is often based on census records. For example, we can compute an age-adjusted estimate of hypertension based on the 2010 age distribution of US adults (which is the middle year for the NHANES estimates considered — i.e., 2005-2015). Based on the 2010 Census, there were 234,564,071 adults in the US. The table below indicates the number of adults in the 2010 Census in each of these age groups (population_2010) as well as a column that shows what proportion of the total US population from 2010 fell into each age group (pop_prop_2010).

For example, for the 18 to 44 age group this is calculated as 112,806,642/234,564,071). The result is 0.48 for the 18 to 44 age group — indicating that about 48% of the US adult population was between 18 and 44 in 2010.

In the provided worksheet, complete the column labeled pop_prop_2010 using the technique described in Step 3.

Step 4

Weight the Age-Specific Prevalence: Now, we’re ready to address the diversity in the age distribution of different populations. Since the risk of hypertension varies significantly with age, simply comparing crude prevalences may be misleading, especially when the age distributions of the populations in question differ. To account for this, we multiply the age-specific prevalence rate for hypertension within each age group by the proportion of that age group in the chosen standard population (in this case, the 2010 U.S. population). This process gives us what’s known as a weighted age-specific prevalence.

For the age 18 to 44 group, the weighted prevalence is calculated as the the percentage of people in this age category with hypertension (23.1) multiplied by the proportion of that age group in the chosen standard population (.4809). This yields a weighted prevalence of 11.11%. In your worksheet, note that I’ve recorded this in the table.

In the provided worksheet, calculate the weighted prevalence for the other age categories.

Step 5

Calculating Age-Adjusted Prevalence: Once we have the weighted age-specific prevalences, we sum these values across all age groups. The sum represents the age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension for our population, had it been comprised of the same age distribution as the standard population utilized (2010 U.S. population). In this example, this is obtained by summing the weighted estimate column in your worksheet.

Please sum the weighted age-specific prevalences and record the age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension for US adults in the designated cell.

If you completed all tasks correctly, you should obtain an age-adjusted estimate of 44.4%. This is our age-adjusted estimate of hypertension based on the 2010 age distribution of US adults.

What Does the Weighted Age-Specific Value Represent?: Each weighted age-specific value reflects the contribution of that age group to the overall hypertension prevalence, as if the age distribution was uniform across all populations being compared. It’s a hypothetical scenario that allows us to isolate the effect of hypertension prevalence from the effects of differing age distributions.

Why Sum the Weighted Values?: Summing these weighted age-specific values gives us an overall prevalence rate that is adjusted for age differences. This age-adjusted prevalence is crucial for making fair comparisons between populations or over time within the same population. It provides a single, standardized measure that accounts for the fact that the risk of hypertension increases with age, and that different populations may have different age structures.

By following these steps, we obtain an age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension that allows for equitable comparisons across different populations or time periods, irrespective of their age distributions. This method ensures that our comparisons are not misrepresented by variations in population age structures, thus offering a clearer, more accurate picture of the true prevalence rates of hypertension in a desired population (i.e., US adults based on the 2010 Census).

In this case, we find that the crude and age-adjusted estimates are very similar. This is to be expected in this example because NHANES attempts to sample participants proportional to the US population across age groups. To demonstrate this, the pie chart below compares the proportion of people in each age group in NHANES (pooled across years 2005 to 2015) with the selected standard population proportions used to calculate the age-adjusted prevalence (i.e., from the 2010 Census).

A more complex example to compare groups

Age standardization can be important because age is a significant risk factor for hypertension, and populations can vary widely in their age compositions. In our simple example there wasn’t much of a difference between the crude and age-adjusted prevalence because the distribution of age in the NHANES sample used is very similar to the distribution of age in the 2010 Census (our selected standard population).

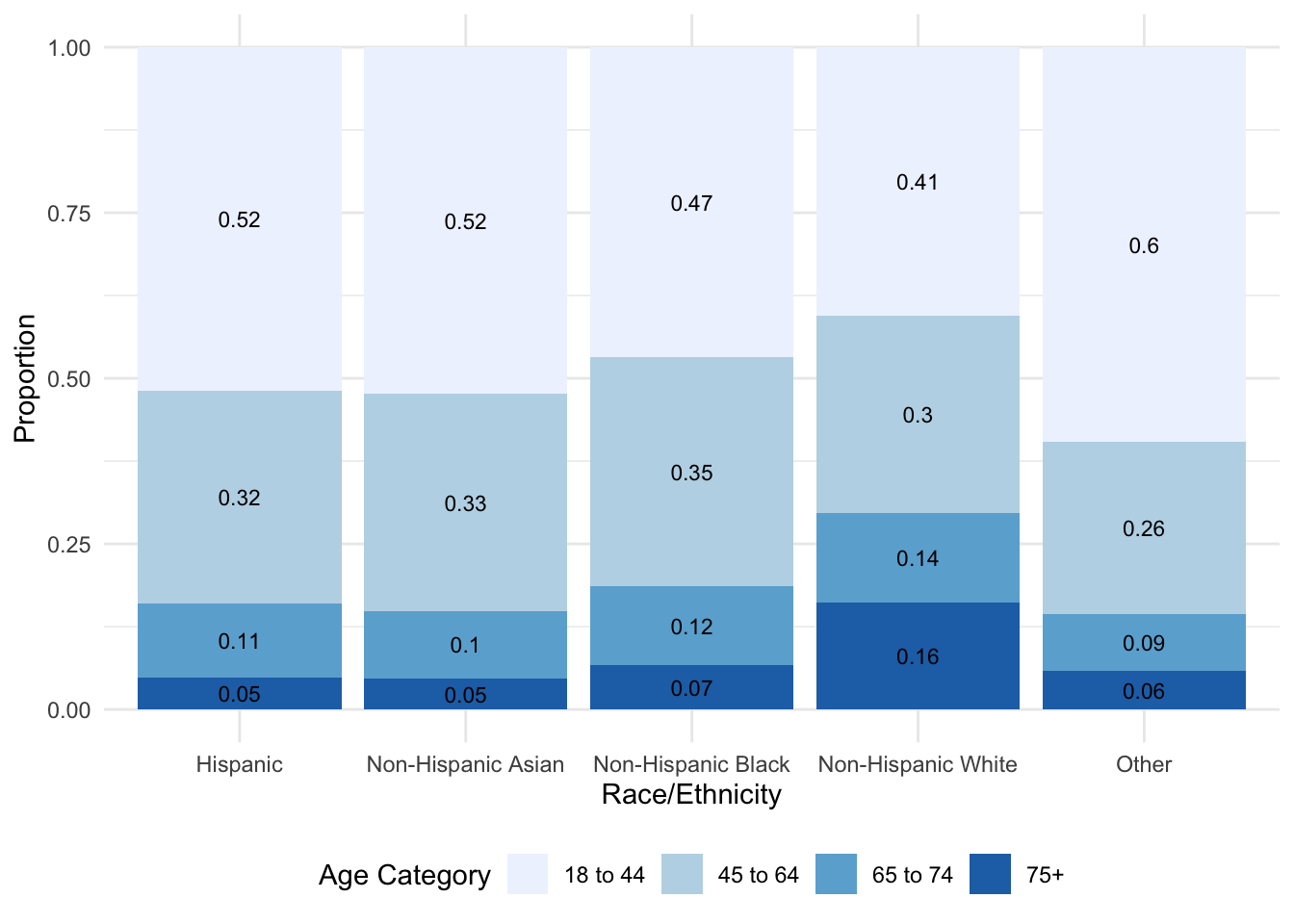

Let’s look at a slightly more complex example where age standardization matters more. In this case, we’ll consider the prevalence of hypertension among US adults as a function of race/ethnic group. Age-adjustment in this context is particularly important because the age distribution of different race/ethnic groups can differ. For example, the graph below presents the proportion of people who fall into each of the 4 considered age groups as a function of race/ethnicity in the NHANES data (note that in this stacked bar graph, the same information that was in the pie charts above is presented — however, the estimates are presented for each group, and a bar replaces the pie).

As observed in the graph, there are notable differences in the age distributions across race/ethnic group. One obvious difference is the proportion of people 75 or older. Among Non-Hispanic White participants — about 0.16 (i.e., 16%) of the participants are in this oldest age group, where the proportion is much smaller for all other race/ethnic groups. For example, about 5% of the Hispanic participants and 7% of the Non-Hispanic Black participants are 75 or older. What other differences in the age distribution do you see?

Because age and hypertension are clearly linked — when comparing the prevalence of hypertension across race/ethnic groups, the crude prevalence may be misleading because the age distributions differ substantially. Instead, if we desire to equate (or hold constant) age by calculating the age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension across race/ethnic groups, we can more accurately compare the burden of hypertension across different groups of people irrespective of the age distribution of the population. It helps to ensure that differences in observed rates are due to differences in the risk of disease, rather than differences in the age structure of the populations being compared. This leads to more informed public health decisions and policies. Let’s take a look at how we can extend what we did in our simple example to accomplish our goal in this context.

Compute crude estimates of hypertension for each race/ethnic group

In the NHANES sample, the crude estimates of hypertension prevalence across race/ethnic groups are presented in the table below, where estimate provides the crude prevalence of hypertension across race/ethnic groups.

Compute age-adjusted hypertension prevalence for each race/ethnic group

To calculate the age-adjusted hypertension prevalence for each race/ethnic group, we take the same approach we took for the simple example. However, rather than working through the process once, we must work through the process for each race/ethnic group. Importantly, we use the same standard population for all groups. This is critical so that we can compare the prevalence of hypertension across race/ethnic groups holding constant age distribution. Notice that the scores for pop_prop_2010 are the same as those we used in the simple example, and they are the same for each race/ethnic group.

Recall that we first multiply the age-specific estimate by the standard population proportion. Then, we sum these weighted estimates within each race/ethnic group to arrive at the age-adjusted hypertension prevalence estimates. For example, for non-Hispanic White adults, the age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension is calculated as: 11.11 + 19.21 + 6.75 + 6.48 = 43.5%.

Using the backside or your worksheet (labeled Part 2), in the table labeled Age-adjusted prevalences of hypertension by race/ethnic group — fill in the age-adjusted estimate for each race/ethnic group, following the method described for non-Hispanic White adults above.

Now that your work is complete, let’s review the completed example. The table below combines the crude and age-adjusted estimates of hypertension prevalence across race/ethnic groups so that we can see a side by side comparison.

The table shows both crude and age-adjusted hypertension prevalences for the race/ethnicity groups. The crude hypertension (crude_estimate) prevalence is a straightforward calculation of the proportion of individuals with hypertension in each racial/ethnic group without accounting for the age structure of the population. In contrast, the age-adjusted hypertension (age_adj_estimate) prevalence takes into account the age distribution of the population, providing a prevalence rate that would exist if the population had the same age distribution as the standard population. Recall that Non-Hispanic White individuals were over-represented in the 75+ group in the NHANES study — thus, when age is adjusted to the standard population, then the age-adjusted hypertension prevalence for this group is lower than the crude estimate. The other race/ethnicity groups have a age-adjusted prevalence that is higher than the crude prevalence. Thus, our age-adjusted estimates display the prevalence of hypertension if all race/ethnic groups had the same age distribution.

Crude estimates are valuable because they provide a straightforward, initial snapshot of the data, showing the raw prevalence of a condition within different groups. This can be useful for quickly identifying groups with high overall rates of a condition. However, age-adjusted estimates are crucial for making fair comparisons between groups with different age distributions. By accounting for age, these adjusted estimates give a clearer picture of the true prevalence, allowing for more accurate public health assessments and resource allocation. For example, the crude prevalence might overestimate hypertension rates in a population with a larger proportion of older individuals, while the age-adjusted prevalence provides a standardized comparison across populations.

Other examples where adjustment may be important

In health and psychological research, making accurate comparisons between groups often requires adjusting for various factors (i.e., often referred to as confounding factors). These adjustments help to isolate the effect of the primary variable of interest on the outcome, providing a clearer understanding of the underlying relationships.

In our last example, we examined how the prevalence of hypertension (the outcome measure) differed across race/ethnic groups (the grouping variable), while adjusting for age. Here, let’s consider three additional examples from psychological and health research, each illustrating the importance of adjusting for a specific confounding variable when comparing groups on different outcome measures.

Example 1: Psychological Well-being and Income Level

Outcome Measure: Psychological well-being score (measured by a standardized questionnaire)

Grouping Variable: Income level (low, medium, high)

Adjustment Variable: Age

- Why Adjusting for Age is Important: Psychological well-being can vary significantly across different age groups due to life stage, experience, and age-related challenges. Younger individuals might experience different stressors compared to older adults. Adjusting for age ensures that the observed differences in well-being across income levels are not simply due to age-related variations, allowing for a clearer understanding of how income level independently affects psychological well-being.

Example 2: Physical Activity and Obesity

Outcome Measure: Body Mass Index (BMI)

Grouping Variable: Level of physical activity (sedentary, moderately active, highly active)

Adjustment Variable: Dietary Intake

- Why Adjusting for Dietary Intake is Important: Diet plays a crucial role in determining body weight and BMI. Individuals with different levels of physical activity might also have varying dietary habits that could independently affect their BMI. By adjusting for dietary intake, researchers can more accurately attribute differences in BMI to physical activity levels, rather than to confounding effects of diet, leading to a more precise understanding of the relationship between physical activity and obesity.

Wrap up and submit

Follow the directions on Canvas for the Apply and Practice Assignment entitled “Crude and Adjusted Statistics Apply and Practice Activity” to get credit for completing this assignment.